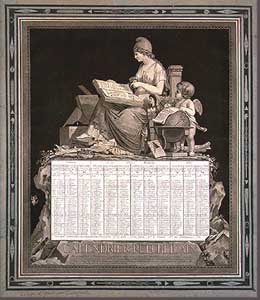

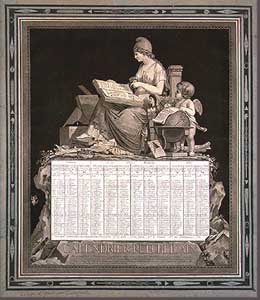

In October 1793, the Jacobin government gave France a time system reflective of the new political realities. The Jacobins retrospectively set the first day of the first year as 22 September 1792, the day the French national government abolished the monarchy. Each year thus began in September, and the calendar endured into the Napoleonic era before it was abandoned. Revolutionary Calendar years were divided into 12 months of 30 days, followed by five or six additional days. The additional days at the end of the year (sans culottides) were Virtue Day, Genius Day, Labor Day, Reason Day, Rewards Day, and Revolution Day (the leap day). Leap years (with a sixth additional day) occurred on years III, VII, and XI. This calendar was in effect until December 31, 1805, proving less durable than the metric reforms. |

Vendémiaire, the month of vintage, mid-September through mid- October

Brumaire, the month of fog, mid-October through mid- November

Frimaire, the month of frost, mid-November through mid- December

Nivôse, the month of snow, mid-December through mid-January

Pluviôse, the month of rain, mid-January through mid-February

Ventôse, the month of wind, mid-February through mid-March

Germinal, the month of budding, mid-March through mid-April

Floréal, the month of flowers, mid-April through mid-May

Prairial, the month of meadows, mid-May through mid-June

Messidor, the month of harvest, mid-June through mid-July

Thermidor, the month of heat, mid-July through mid-August

Fructidor, the month of fruit, mid-August through mid- September

|  |

Return to

Return to